The information on this page is not meant to be a substitute for veterinary care. Always follow the instructions provided by your veterinarian.

8 Cat Diseases you Can Prevent with Vaccination and Deworming

1. Rabies (this can be spread to people)

2. Feline panleukopenia (feline distemper)

3. Feline herpesvirus infection

4. Feline calicivirus infection

5. Feline leukemia (FeLV)

6. Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) infection

7. Heartworm disease

8. Intestinal worms (roundworms, hookworms, whipworms, tapeworms, etc., some of which can also infect people)

12 Dog Diseases You Can Combat with Vaccination and Deworming

12 Dog Diseases You Can Combat with Vaccination and Deworming

1. Rabies (this can be spread to people)

2. Canine parvovirus infection ("parvo")

3. Canine distemper

4. Leptospirosis

5. Canine adenovirus-2

6. Canine parainfluenza

7. Canine enteric coronavirus

8. Canine influenza

9. Lyme disease

10. Bordetella ("kennel cough")

11. Heartworm disease

12. Intestinal worms (roundworms, hookworms, whipworms, tapeworms, etc., some of which can also infect people)

What You Should Know About Preventing Fleas and Ticks

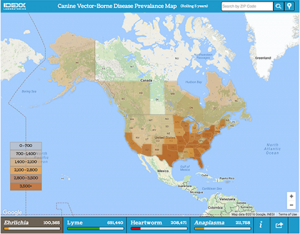

Click the map below to learn more about vector-borne disease in our area

The thought of insects crawling on your skin and living off your blood probably, well, makes your skin crawl. Yet, too often as pet owners, we allow fleas and ticks to treat our pets like bed-and-breakfasts. And it is only after these pests make themselves at home that we might realize showing them the door can be difficult, expensive and painfully slow.

Fleas and ticks aren’t just irritating and distasteful; they can lead to medical problems. Flea allergies can cause severe itching and skin damage; fleas can also carry the causative agents of cat-scratch disease, while ticks carry the organisms that can lead to debilitating illnesses like Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. So it’s crucial to continuously and effectively prevent infestations of these parasites for the health and safety of our pets, our families and ourselves.

Consider the life cycle of the common flea: The average female can lay 40 to 50 eggs daily. The eggs develop into maggot-like larvae and progress to a cocoon stage called pupae. These pupae wait several weeks to months for the ideal temperature and humidity to mature into adult fleas. That single adult flea you find on your pet represents about 5 percent of the total flea problem in your home; eggs, larvae, and pupae comprise the rest. Your pet — and your home — can be infested before a single flea is found. And finding them can be tough, especially on cats, because of their constant grooming. That’s why a one-time treatment for fleas isn’t usually enough. Pet owners often discover a flea problem because of a pet’s severe itching, which sometimes is due to flea allergy dermatitis — a sensitization to the flea’s saliva when it draws a blood meal. No pet is safe from fleas and their bites, but not all pets are hypersensitive to them. This means severe infestations can occur without your dog or cat showing any obvious discomfort. Therefore, it’s best to use preventive tactics to help keep fleas from infesting your pet and home in the first place. To do this, speak with your veterinarian about safe flea-control products that you can administer to your pet year-round. Some products are administered once a month, but other products provide longer-lasting protection. Ask your vet about the best choice for your pets. Consistent use of safe prevention products is the primary method of managing fleas. Newly hatched young adult fleas usually feed right away. If your pet has been treated with an appropriate flea product when these adult fleas emerge, you can help break the cycle of infestation. (Remember to treat all of the pets in the house, regardless of whether or not they’re itching.) Treating your pet’s environment is also an important part of controlling and preventing flea infestations. Fleas lay their eggs on your pet, but the eggs usually fall off. Once in the environment, they molt into larvae and develop into the pupae stage. Larvae don’t survive well in sunlight, preferring instead to hide in dark, protected areas like deep carpet or pet bedding. Therefore, focus on treating the places your pet likes to rest, especially those that are out of sunlight, like a resting place in the shady area of the yard, your pet’s blanket or pillow — or even your bed (ick). Frequent cleaning or vacuuming can help reduce the pupal and larval stages of fleas in the carpet, and many flea control products used on pets also kill eggs and larvae. But don’t forget that fleas can gain access to your house or yard in many ways, including wildlife, neighborhood cats and you, just to name a few. Also remember that if your dogs or cats are allowed access to other areas — such as parks, nature areas, crawl spaces or even the neighbor’s yard — they’ll have ample opportunity to encounter fleas. Therefore, even if you’re treating your pet, areas of your home and yard may also need regular attention. Like fleas, ticks can now be found throughout most of the country. Though the severity of tick infestations varies by region, ticks are now spreading into areas that previously had very limited tick problems. Unlike fleas, ticks may not cause dramatic irritation when they attach to your pet’s skin. This lets the tick slowly fill with blood without interference. Before feeding, ticks are often small and easily overlooked; once a tick has eaten and is engorged with blood, it grows in size and often looks bloated. These bloated ticks are usually easier to spot (depending on species—some of them can still be very small), but can be difficult to remove —especially if you aren't used to doing it. If you see a bloated tick, your best bet is to visit your veterinarian so she can remove it and check for any additional ticks. There are several species of ticks that pose a risk to pets and people. Ticks can be hosts to several types of disease-producing organisms that can be transmitted to pets or people while the tick is feeding. These organisms can cause illnesses like Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Again, the lesson here is that it’s best to protect your pets — and yourself — from ticks rather than react to them after the fact. Most ticks lurk in tall grass or low-hanging bushes and crawl onto pets or people as they walk by. The tick can then travel on the host — that’s you or your pet — to find a suitable place to attach and feed. Considering how stealthy these travelers are, the most reliable plan is to keep your pet on an effective tick preventive all year. Conveniently, many products combine protection from ticks with flea protection. Your veterinarian can recommend a product that is safe and appropriate for your pet. You can also help prevent ticks by keeping the grass and bushes in your pet’s outdoor area mowed and trimmed. If you’re hiking, camping or playing in untended and possibly tick-infested outdoor areas, wear long pants, long-sleeved shirts and headgear to help prevent tick exposure. Afterward, be sure to check both your pets and your family for ticks. Some circumstances may seem like they’d be guaranteed flea and tick free, but this is not so. There is no such thing as a completely risk-free situation. Pets need prevention in every situation. Think your indoor pet is safe? Think again. You’ve seen bugs inside your house — fleas and ticks can sneak indoors, too. Even pets who don’t venture outside — such as an indoor cat or a dog who only goes in the yard for potty breaks — are at risk of flea and tick infestation. Granted, their infestation chances are lower than those of outdoor pets, but you can help protect them by using safe and effective flea and tick control products year-round. And don't assume that there's a flea- and tick-free season. Fall and winter may seem like distant memories at this time of year, but they’re not to be forgotten when it comes to parasite prevention. Fleas and ticks have a way of popping up in the colder months. In fact, flea numbers can surge in the fall in temperate climates. What’s more, fleas enjoy a wonderful, climate-controlled environment inside your house year-round. They can gain inside access by hitching a ride on outside sources, such as you and your pets, or adult fleas can develop from eggs or larvae that were already hiding in your house. Don’t forget that ticks are extremely tough, too, and can often survive outside even during the winter months. The only way to ensure your dog or cat is safe from fleas and ticks is to keep him on a parasite preventive all year. Today’s highly effective parasite preventives each work a little differently to keep fleas off your pets; your veterinarian can recommend a product that best suits your pet’s health needs and your lifestyle. Here’s a look at the differences between oral products (which your pet eats) and topical products (which you apply to your pet’s skin). There are also some effective collars that you may want to ask your vet about. Oral Flea Control Topical Flea Control Remember this mantra: When it comes to fleas and ticks, it’s best — and safest — to prevent an infestation than it is to deal with the consequences. Your veterinarian, as an expert in parasite control and prevention, can recommend the best products to help prevent infestation. (Keep in mind that not all insecticides are safe for both cats and dogs of all sizes, so carefully follow your veterinarian’s recommendations.) With a little effort and a year-round prevention plan, you can keep your pets virtually parasite free — and help ensure that your home sports a “no vacancy” sign when it comes to fleas and ticks.Fleas: The Prolific, Perplexing Parasite

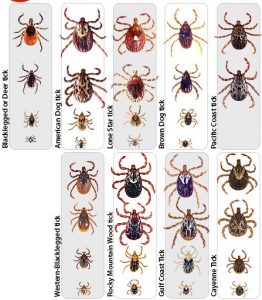

Ticks: Expanding Their Disease-Carrying Reach

The Risk-Free Myth

Keeping Fleas off Pets: Your Options for Preventives

Stop Fleas and Ticks Before They Start

Pet First Aid Tips

What would you do if

...your dog ate the bag of semi-sweet chocolate chips that was left out on the kitchen counter?

...your cat had a seizure right in front of you?

...your dog fell down the stairs and started limping?

...your cat was overheating on a hot summer day?

View our Pet First Aid brochure To avoid the feelings of panic that may accompany these situations, we recommend the following steps to better prepare you for a pet medical emergency. The following links summarize the basics you need for giving first aid care to your pet. Always remember that any first aid administered to your pet should be followed by immediate veterinary care. First aid care is not a substitute for veterinary care, but it may save your pet's life until it receives veterinary treatment. First aid supplies How to handle an injured pet Basic pet first aid procedures First aid when traveling with your pet Pets and disasters

Our handy checklist tells you all the supplies you should have on hand for pet first aid. Print out a copy to use for shopping, and keep a copy on your refrigerator or next to the first aid kit for your family, for quick reference in emergencies.

Knowing how to comfort an injured pet can help minimize your pet's anxiety and also protect you and your family from injury.

Read our simple instructions for providing emergency first aid if your pet is suffering from poisoning, seizures, broken bones, bleeding, burns, shock, heatstroke, choking or other urgent medical problems. Print out a copy to keep with your pet emergency kit.

A few simple steps can better prepare you to help your pet in first aid situations while you are traveling. Remember: pet medical emergencies don't just happen at home.

Whether confronted by natural disasters such as hurricanes, or unexpected catastrophes such as a house fire, you need to be prepared to take care of your animals. A pre-determined disaster plan will help you remain calm and think clearly.Additional pet first aid links

!!Fleas!! Myth vs Fact!

!!Fleas!! Myth vs Fact!

My house has no carpet, so I do not have to worry about fleas in my home.

Fact: Flea eggs will drop off the pet and accumulate in the cracks of hardwood floors and along the baseboards. The larvae will then move deep into these crevices to avoid exposure to light. Fleas can survive and multiply in most environments.

I do not see fleas on my pet, so there must not be any.

Fact: Visible adult fleas are only a small portion of the infestation. Fleas exist in the environment as ≈57% eggs, 34% larvae, 8% pupae, and 1% adults. Fleas are difficult to see on many types of hair coats. They can be harder to see on cats, who are very good at removing the fleas when they groom.

My pet never leaves my yard, and my lawn is short and well maintained.

Fact: Fleas will survive in any shady, moist environment where pets rest.

I do not need to use preventives during the winter months.

Fact: Fleas can survive for 10 days at 37.4oF. In cold climates, adult fleas survive on the warm bodies of dogs, cats, and other mammals, and indoors within pupal casings as pre-emerged adults.

I give my dog garlic as a natural flea preventive.

Fact: Garlic ingestion is an ineffective flea remedy that can have negative health effects. Garlic toxicity can result in oxidative damage to erythrocytes, which may lead to Heinz body formation, hemolytic anemia, methemoglobinemia, and impaired oxygen transportation.

Why you Should Not Feed Grain Free Diets

FDA Investigation into Potential Link between Certain Diets and Canine Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Check out the links below to learn more:

https://www.aaha.org/publications/newstat/articles/2021-08/new-clues-to-diet-associated-dcm-in-dogs/

Bathing Your Dog

Every pet owner has an olfactory (smell) memory that triggers their gag reflex, “I’ve never smelled anything like it! (S)He must have rolled in something dead!Odors that defy classification have an obvious solution; bathe the dog. Soap choice is where the confusion starts. In some situations it seems nothing but the harshest solvents will be adequate to clean your pet. It may also seem reasonable to use dish soap or a product designed for human hygiene, such as shampoo. “Harsh chemicals aren’t necessary,” assured Terese DeManuelle, a veterinary dermatologist from Portland, Oregon. “A mild hypoallergenic soap that’s formulated for veterinary use is all you need.” “Formulated for veterinary use” means a product that’s designed to work with a dog’s body. While dish soap or your favorite shampoo might strip away the dirt, and more importantly the odor, from your pet’s coat, it will also strip natural oils from their fur and may irritate their skin.

All grooming products (human and animal) are designed to maximize cleaning and minimize irritation. Human products work best on human skin and veterinary products are designed to work best on dog skin. The chemistry of a dog’s skin and fur are different than the chemistry of a human’s skin and hair. In addition to the odor- provoked “emergency bath” Dr. DeManuelle notes it’s safe to bathe your dog with veterinary shampoo once a week. However, if the veterinary shampoo you’re using contains any medication or insecticide, follow the instructions provided by your veterinarian. Prescription shampoos treat specific problems and may necessitate bathing more or less frequently than once a week. A final insight pertaining to bathing your pet is to comb their coat prior to bathing. Wet fur mats more than dry fur so a wet tangled coat is harder to brush out and will take longer to dry. This small detail can save you time and prevent an uncomfortable brushing for your pet. After a bath your dog will smell good, look good, and probably feel good. Make sure your dog is dry before you allow it back outside or it will feel good enough to dry itself. It will streak from the tub straight outside to find a new exotic aroma to frolic in and bring home to share. This Pet Health Topic was written by Sarah Hoggan, Washington State University, Class of 2001.

An Overview of Cancer

Cancer is caused by uncontrolled and purposeless growth of cells in the body. Other terms for cancer are malignancy, tumor and neoplasia. Cancer can arise from any tissue in the body so there are many types of cancer.

Some forms of cancer have the ability to spread to other sites in the body which are often far from the original site. This happens when cancer cells enter the blood or lymph vessels and are then carried to other organs. Cancers with this type of behavior are considered malignant.

Often, it is the spread of a cancer that causes the greatest problems. When a cancer has spread in this fashion, it is said to have metastasized. Some cancers lack the ability to metastasize, but may cause significant damage due to growth and invasion into local tissues. Tumors that do not metastasize and are not invasive are considered benign. Tumor is a general term for cancer whether it is benign (“good cancer”) or malignant (“bad cancer”). Oncology is the branch of medicine dedicated to the study of cancer, and the people treating your pet at WSU are Oncologists and Oncology nurses. The first task for the veterinarian is to determine the extent of the tumor which is a process called tumor staging. Staging information is vital for several reasons including: 1. determination of your pet’s prognosis (i.e., the expected outcome for your pet from the illness) and, To gather information that can help to determine the extent of the cancer, your veterinarian will need to evaluate your pet by several methods. These usually include blood tests (e.g., blood count, chemistry profile), urinalysis, radiographs (x-rays), tissue aspirate (a sample taken with a fine needle) and biopsy. Tests which your veterinarian may have performed might be repeated at WSU due to the changing nature of your pet’s illness. In addition, as indicated for specific patients, other testing procedures may include: ultrasound, specialized radiologic studies (e.g., CT scan, dye contrast studies), bone marrow aspirate, lymph node aspirate, endoscopy (direct examination of the stomach, colon or bronchi with a specialized scope), and immunologic studies. It is important to note that medicine is not an exact science and despite these staging procedures, it is still possible to fail to recognize small sites of tumor or the presence of tumor in organs that are difficult to study. Once the tumor staging has been completed, your veterinarian will better be able to discuss treatment options for your pet. The goal of such therapy will also be discussed. Tumors that have metastasized extensively are usually not curable. Therefore, the objective of therapy for these animals is palliation (i.e., afford relief of signs without providing cure, and possibly, prolong life). Localized tumors that are not deeply invasive have the best chance to be cured. There are several types of therapy used to treat cancer in dogs and cats at WSU. These include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and immunotherapy. For some tumors, treatment will consist of a single type of therapy, while combination therapy may be recommended for other types of cancer or for animals with a more advanced stage of disease. On occasion, due to the rarity of a particular tumor, a precise treatment recommendation may not be known. In an effort to test newer (and hopefully more effective) forms of therapy, you may be asked to enroll your pet in an investigative clinical trial. The purpose of such a trial is to learn more about the specific type of treatment (that may be of value to humans and other pets with cancer) as well as hopefully providing a benefit to your pet. Only pet owners of animals with tumors for which there is no effective treatment, or tumors that have not responded to conventional treatment will be offered investigative therapy for their pets. Treating animals with cancer is not appropriate for every pet owner. It takes a strong commitment on the part of the owner. Therapy requires frequent trips to the veterinary hospital and can be expensive. For some forms of cancer treatment, once begun treatment is never stopped during the animal’s life although the frequency of these treatments can be decreased. Your veterinarian cannot do it alone since treating pets with cancer is truly a team effort and the pet owner is on the team. It is important for you to present your pet for treatment precisely when requested to do so by your veterinarian since the timing of cancer therapy is critical for obtaining an optimal outcome. In addition, medicines to be given to your pet at home should be administered by you exactly as instructed by your oncologist. Any abnormalities or problems you encounter should be reported to your regular veterinarian or oncologist promptly. Always feel free to ask questions and communicate with us. Keep in mind your veterinarian is as concerned about the quality of your pet’s life as you are. The goal of the therapy is to keep your pet happy and minimize discomfort. Although some animals may experience transient discomfort from therapy, treatment of most pets with cancer can be accomplished without major distress or detraction from your pet’s enjoyment of life. Just because an animal has been diagnosed with cancer does not mean its life is immediately over. Your commitment to your pet and your veterinarians dedication to providing state-of-the-art care will work together to keep your pet as happy as possible.

Tumor Evaluation (Work-up): Tumor Staging

2. formulation of a plan for treatment.Cancer Therapy

Should You Treat Your Pet?

Chronic Kidney Disease and Failure

Chronic kidney disease is defined as kidney disease that has been present for months to years. Chronic renal disease (CRD), chronic renal failure (CRF), and chronic renal insufficiency refer to the same condition.

CKD is not a single disease. There are many different causes of CKD but by the time the animal shows signs of kidney disease the cause may no longer be apparent. Some potential causes of CRF include:

Often the cause of CKD is unknown. The microscopic unit of the kidney is called the nephron. Each kidney contains thousands of nephrons. When the pet is young and healthy not all nephrons are working all of the time; some nephrons are held in reserve. As the animal ages or if the kidneys are damaged, some nephrons die and other resting nephrons take over the work of those that die. Eventually all the remaining nephrons are working. When there are no extra nephrons remaining and kidney damage continues the pet will start showing signs of CKD. Because of this stepwise loss of nephrons the kidneys are able to "hide" the fact that they are damaged until the damage is severe. When 2/3 of the nephrons have been lost the pet is no longer able to conserve water and the pet passes larger amounts of dilute urine. By the time a pet has an elevation in the waste product creatinine in its blood, 75% of the nephrons in both kidneys have been lost. When blood flows through the kidneys, the kidneys act as a complex filter that removes from blood wastes that are generated from break down of food, old cells, toxins or poisons and many drugs that are given for treatment of other diseases. The wastes are removed with water as urine. Waste products than can be measured in the blood include creatinine and urea nitrogen but there are many other waste products that are not measured by blood tests. The kidneys also acts as a filter to keep "good" substances in the blood. The kidneys regulate the amount of water in the blood by excreting extra water and retaining water to prevent dehydration by varying the amount of urine that is produced. The kidneys help regulate blood pressure by saving or eliminating sodium based on how much sodium the pet is eating. The kidneys help regulate calcium and vitamin D which keep bones strong. The kidneys produce a substance that helps with the creation of new red blood cells. Because the kidneys have so many functions, when the kidneys are not working normally, there are many signs that the pet may show. By the time the pet shows signs of CKD, the damage is severe. There is no cure for CKD. The remaining nephrons are working so hard that with time they will fail as well. CKD is usually fatal in months to years but various treatments can keep the pet comfortable and with a good quality of life for months to years. Because the kidneys perform so many functions, the signs pets with CKD show can vary quite a bit. The signs may be severe or may be subtle and slowly progressive. Despite the chronic nature of the disease, sometimes signs appear suddenly. Some of the more common signs of CKD include: Signs you may see if you examine your pet include: dehydration, weight loss, pale gums and ulcers in the mouth. The signs seen in pets with CKD and the findings on examination are not specific for CKD and may be seen with many other diseases so blood and urine tests are needed to make a diagnosis of CKD. Abnormalities that are often seen on diagnostic blood and urine tests include: Sometimes bruising occurs where the blood sample was drawn as pets with CKD may have platelets that are less sticky than normal (normal platelets prevent bruising). A diagnosis of CKD can usually be made based on the signs, physical examination and blood and urine tests but other tests may be performed to look for an underlying cause for the CKD and/or to "stage" the CKD. The severity of chronic kidney disease (CKD) can be estimated based on blood waste product elevation and abnormalities in the urine such as the presence of protein. The International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) has developed a method to estimate the stages of CKD. Stages are numbered 1 through 4 where one is the least severe and four is the most severe. The higher the stage number also generally corresponds to the greater number of symptoms seen in the pet. Some treatments are recommended to be started when the pet has a certain stage of CKD. See the IRIS site for full details on staging. The severity of the pet's signs will determine what treatments are needed. Not all treatments presented below may be needed or appropriate for each pet with a diagnosis of CKD. Treatments may also be started incrementally (a few treatments are started and then based on patient response, additional treatments may be added later). The information below is not meant to be a substitute for veterinary care. Pets with severe signs may be hospitalized for fluid and intravenous drug treatment to reduce the amount of waste products in their body. Many pets with CKD will feel better in response to treatment with IV fluids but if the kidney disease is extremely severe the pet may not respond to treatment. Those pets who are still eating and not showing severe signs are treated with a variety of treatments, often introducing treatments incrementally as new signs develop. The treatment approach is often called "conservative" compared to more aggressive treatments such as hospitalization for fluid therapy, dialysis or kidney transplantation. Remember that CKD is not a disease that can be cured. Treatments are designed to reduce the work the kidneys need to perform, to replace substances that may be too low (such as potassium) and to reduce wastes that accumulate such as urea (generated by the body from proteins) and phosphorus. The initial response to conservative therapy may be relatively slow, taking weeks to months to see a response. Diet Protein restricted diets are less palatable than higher protein diets. Pets with CKD that are still eating are more likely to accept a change in diet to a protein restricted diet than are pets who are very ill and refusing most foods. Protein restricted diets are more expensive than higher protein diets. There are many pet food companies that sell kidney diets. Dr. Tony Buffington at the Ohio State University is a good source of information on available diets. http://vet.osu.edu/1442.htm select a species, a diet form and select Reduced Phosphorous/Protein for a list of diets for pets with kidney disease. Homemade diets can be fed but it is best to work with your veterinarian to formulate a diet that is balanced. It is generally agreed that feeding renal failure diets to dogs and cats with kidney disease improves their quality of live and may minimize the progression of the disease resulting in a longer life span. Studies that evaluate the effect of dietary changes on quality and quantity of life typically use commercial diets that differ in their composition of protein, phosphorus, sodium and lipids compared to maintenance diets so that positive effects are not attributable to a single component of the diet but rather to a "diet effect". A randomized, double masked, clinical study in 38 dogs with spontaneous stage 3 or 4 kidney disease, half of which were fed a kidney failure diet and the other half a maintenance diet, published in JAVMA in 2002, demonstrated improved quality and increased quantity of life in the group fed the renal failure diet. The results of a study of cats with naturally occurring stable chronic renal failure fed a diet restricted in phosphorus and protein compared to cats with CKD fed a maintenance diet reported a median survival of 633 days for 29 cats fed the renal diet compared to 264 days for 21 cats fed a regular diet. The groups were not randomly determined but based on cat & owners willingness to change to the renal diet. In a study published in JAVMA in 2006, 45 client-owned cats with spontaneous stage 2 or 3 CKD were randomly assigned to an adult maintenance diet (23 cats) or a renal diet (22 cats) and evaluated for up to 24 months. Findings included: Water Water soluble vitamins like B and C are lost in greater amounts when the pet is urinating greater amounts. Kidney diets contain increased amounts of water soluble vitamins so additional vitamins do not need to be given unless a homemade diet is being fed. Potassium Phosphorus, calcium and PTH Kidney diets typically contain reduced phosphorus and an appropriate amount of calcium but if phosphorus remains elevated when the pet is eating a kidney diet then phosphorus can be tied up in the intestinal tract so it can be eliminated in the stool. Intestinal phosphate binding agents include aluminum carbonate, aluminum hydroxide, aluminum oxide, calcium citrate, calcium acetate and calcium carbonate and sevelamer hydrochloride. Phosphate binding agents which contain calcium should not be used until blood phosphorus is normal to prevent calcium and phosphorus from combining and precipitating in tissues including the kidneys. It is not usually necessary to give additional calcium but if a pet has low blood calcium, the phosphorus should be normalized before giving calcium. Even when blood phosphorus is normalized, PTH levels are still higher than normal. The administration of low doses of vitamin D (1, 25 dihydroxycholecalciferol [calcitriol]) will suppress PTH and possibly slow the rate of progression of kidney deterioration. It is not 100% agreed that giving your pet calcitriol will slow the deterioration of the kidneys. Here are some web sites on using calcitriol http://members.bellatlantic.net/~vze2r6qt/calcitriol/ Acidosis Sodium High blood pressure (hypertension) Anemia Anemia can be treated by blood transfusion or by the administration of human erythropoietin. Erythropoietin is very effective in increasing PCV but because human erythropoietin is not exactly the same as dog and cat erythropoietin, over time, the pet may form antibodies that cause the medication to become ineffective. Canine and feline erythropoietin are currently being studied. Fats/lipids Subcutaneous Fluids Lack of Appetite Vomiting Drugs used to treat other diseases Antibiotics You are in the best position to judge what is stressful to your pet. When a pet is stressed they may drink and eat less than normal. Reduced water intake is detrimental to diseased kidneys. When possible, keep your pet calm. That might mean for example: having an in-home pet sitter if your pet is stressed by boarding, removing the pet from the household during a party or limiting contact with other animals if these situations appear to be a source of stress for your pet. Extremes in heat or cold are stresses. Certain drugs such as prednisone/cortisone make the kidneys work harder.

Structure of the kidneys

What do the kidneys do?

CKD is progressive

Signs of CKD

Less common signs include

Diagnostic Tests

Other tests that may be performed include

What might this test show? The kidneys in pets with CRD are usually small reflecting the death of a large number of nephrons. If the kidneys are large then certain causes for the CKD should be considered such as lymphoma (cancer) of the kidneys, or an uncommon disease called amyloidosis. Some pets with signs of kidney disease who have large or normal sized kidneys may have acute kidney failure rather than CKD. The treatment and prognosis for pets with acute kidney disease differs from the treatment and prognosis of pets with CKD.

What might this test show? A biopsy is not required to make a diagnosis of CKD but the results of a biopsy may show a cause for the CKD. A biopsy is more likely to show specific information when the kidneys are big rather than small. A biopsy can be valuable in pets who develop CKD at a young age or who are of a breed known to develop congenital kidney disease. There may be specific microscopic changes in a kidney biopsy from an animal with congenital kidney disease that may suggest that related animals are also at risk for developing CKD. Knowledge that the cause of CKD is caused by congenital kidney disease does not change the treatment of the affected animal but does provide information for related animals, for example if you should remove them from a breeding program. When a biopsy is planned, usually the biopsy is collected using ultrasound or laparoscopy to see the kidney during the biopsy so that no other organs are damaged during the biopsy.

What might this test show? Bacterial infection is not a common cause of CRD but pets with CKD may develop a bacterial infection as several aspects of the pet's immune system may be less functional when the kidneys are failing. If white blood cells are observed on microscopic examination of the pet's urine, a bacterial culture of the urine should be obtained.

What might this test show? If a pet is going to under go kidney biopsy, tests may be performed in advance to evaluate the ability to stop the bleeding from the biopsy site.Treatment of CRF

Feeding of a kidney diet is usually recommended. Kidney diets contain less protein compared to other diets and the protein is high in quality. It is protein in the diet that is converted to waste products that the kidneys must remove in the urine. The higher the quality of the protein in the diet, the less wastes created for the kidneys to eliminate. Low quality protein requires the kidneys remove more wastes. which makes them work harder. Egg and meat contain higher quality protein; cereal grain protein is of lower quality which leads to more wastes for the kidneys to eliminate. Protein is used by the body to repair cells and tissues that are continually regenerating, so a pet needs some protein in their diet. By feeding a low quantity, but high quality protein diet that contains an appropriate amount of fats and carbohydrates, the pet's body can use the protein for replacing the cells and tissues and use the fat and carbohydrates for energy. Kidney diets also contain a lower amount of phosphorus. Phosphorus accumulates in the blood when the kidneys are diseased. Kidney diets control the amount of other substances that may be too high or too low in patients with CKD such as salt, potassium, magnesium and B vitamins. There are differences in the kidney diets for dogs and cats. When making diet changes it is often beneficial to gradually introduce the new diet by adding increasing amounts of the new diet while reducing the amount of the current diet over 1 to 2 weeks. The pet is more likely to accept a new diet when it is introduced gradually and it is less stressful to the kidneys to gradually adapt to changes in the diet.

body weight

PCV

urine protein-to-creatinine ratio

creatinine

potassium

calcium

parathyroid hormone concentrations.

Because pets with kidney disease cannot conserve water by making concentrated urine, their water intake is very important to prevent dehydration. Make sure they always have plenty of fresh water available. If the pet is not eating well, or is vomiting, then s(he) may not be drinking enough and may get dehydrated. Pets can be encouraged to drink by giving them flavored broths in addition to plain water. The broth should be low in sodium and its best to discuss with your veterinarian other ingredients in the broth to make sure it doesn't contain substances that will make the kidneys work harder.

Lack of appetite and increased loss of potassium in urine may result in low body potassium (hypokalemia). Cats with CKD are more likely to have low body potassium than are dogs. Cats with low potassium may develop painful muscles. Both cats and dogs may be weak when potassium is low. Cat kidney diets contain higher levels of potassium so additional supplementation is probably not needed unless the cat shows signs of muscle pain. Potassium gluconate or citrate can be given by mouth if potassium supplementation is needed. Potassium chloride is acidifying and is not recommended.

Pets with CKD usually have increased blood phosphorus. In health, phosphorus and calcium are controlled by a hormone called parathyroid hormone (PTH). PTH works with vitamin D on the intestine, kidney and bone to keep calcium and phosphorus normal. As the kidneys fail the amount of PTH in the body is elevated and the amount of vitamin D is reduced. Elevated PTH itself may be responsible for some of the signs shown by pets with CKD. PTH draws calcium and phosphorus from the bones which can weaken bones which can lead to bone fracture.

Some pets with CKD will have an acid blood pH. Kidney diets are designed to counteract the acidosis but very sick animals that are hospitalized may need addition treatment to correct the acidosis.

Diseased kidneys are less efficient at regulating sodium and sodium in turn helps control blood volume and pressure. Excess sodium can lead to water retention and not enough sodium can lead to dehydration. When changing diets that contain different amounts of sodium (kidney diets usually have less sodium than regular diets) make the change gradually over several weeks. Use caution when giving your pet table scraps or treats that may be high in sodium.

Many pets with CKD have high blood pressure. High blood pressure can contribute to further decline of kidney function and can occasionally lead to sudden blindness from retinal detachment. Ideally blood pressure should be measured by your veterinarian and hypertension confirmed before giving drugs to treat high blood pressure but measuring true blood pressure in dogs and cats can be difficult. If the pet has an elevation in blood pressure it may be due to the excitement of being examined or due to CKD. The calmer you are able to keep your pet during examination, the more reliable the readings for blood pressure. There are several drugs that may be used to manage high blood pressure including enalapril, benazepril, or amlodipine (and others). Enalapril and benazepril are in a class of drugs called <align="left"> ACE inhibitors and are sometimes used in pets with CKD that have abnormal amounts of protein in their urine even when blood pressure is normal.

The kidneys play a role in producing a hormone called erythropoietin which stimulates the production of new red blood cells. Red blood cells live about a hundred days so new cells are continually being made. Less erythropoietin is made in pets with CKD leading to anemia. The packed cell volume (PVC) (also called hematocrit) is the percentage of blood cells compared to fluid in whole blood. When the PCV is ~20 in cats and ~ 25% in dogs, anemia may contribute to lack of activity and weakness.

Certain types of fats (polyunsaturated omega 6 fatty acids) may slow the decline in kidney function are are often present in kidney diets.

Some cats and dogs with kidney disease may not drink enough to prevent becoming dehydrated and may benefit from the administration of intermittent SC fluids. If your veterinarian feels your pet may benefit from giving subcutaneous fluids, we provide some instructions on how to give SC fluids. See Cat Fluids or Dog Fluids

The accumulation of wastes in the body often decreases appetite. A goal of several of the above treatments is to reduce the amount of wastes in the blood. If the pet remains off food despite above treatments you might try different brands of renal failure diets, warming the food or adding odiferous toppings to entice the pet to eat.

Increased levels of waste products cause the pet to vomit. Your veterinarian may recommend medications that reduce nausea or act directly on brain centers to reduce the urge to vomit.

Because the kidneys are responsible for elimination of many drugs, make sure that your veterinarian is aware of any other medications you are giving your pet as these may accumulate in the body to toxic levels if the kidneys cannot eliminate them.

If the urine shows signs of infection or if a urine culture grows bacteria then antibiotics may be administered. If a urinary tract infection is involving the kidneys, the period of treatment is much longer than a infection of the bladder. Avoiding Stress

Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus occurs when the pancreas doesn't produce enough insulin. Insulin is required for the body to efficiently use sugars, fats and proteins.

Diabetes most commonly occurs in middle age to older dogs and cats, but occasionally occurs in young animals. When diabetes occurs in young animals, it is often genetic and may occur in related animals. Diabetes mellitus occurs more commonly in female dogs and in male cats.

Certain conditions predispose a dog or cat to developing diabetes. Animals that are overweight or those with inflammation of the pancreas are predisposed to developing diabetes. Some drugs can interfere with insulin, leading to diabetes. Glucocorticoids, which are cortisone-type drugs, and hormones used for heat control are drugs that are most likely to cause diabetes. These are commonly used drugs and only a small percentage of animals receiving these drugs develop diabetes after long term use. The body needs insulin to use sugar, fat and protein from the diet for energy. Without insulin, sugar accumulates in the blood and spills into the urine. Sugar in the urine causes the pet to pass large amounts of urine and to drink lots of water. Levels of sugar in the brain control appetite. Without insulin, the brain becomes sugar deprived and the animal is constantly hungry, yet they may lose weight due to improper use of nutrients from the diet. Untreated diabetic pets are more likely to develop infections and commonly get bladder, kidney, or skin infections. Diabetic dogs, and rarely cats, can develop cataracts in the eyes. Cataracts are caused by the accumulation of water in the lens and can lead to blindness. Fat accumulates in the liver of animals with diabetes. Less common signs of diabetes are weakness or abnormal gait due to nerve or muscle dysfunction. There are two major forms of diabetes in the dog and cat: 1) uncomplicated diabetes and 2) diabetes with ketoacidosis. Pets with uncomplicated diabetes may have the signs just described but are not extremely ill. Diabetic pets with ketoacidosis are very ill and may be vomiting and depressed. The diagnosis of diabetes is made by finding a large increase in blood sugar and a large amount of sugar in the urine. Animals, especially cats, stressed by having a blood sample drawn, can have a temporary increase in blood sugar, but there is no sugar in the urine. A blood screen of other organs is obtained to look for changes in the liver, kidney and pancreas. A urine sample may be cultured to look for infection of the kidneys or bladder. Diabetic patients with ketoacidosis may have an elevation of waste products that are normally removed by the kidneys. The treatment is different for patients with uncomplicated diabetes and those with ketoacidosis. Ketoacidotic diabetics are treated with intravenous fluids and rapid acting insulin. This treatment is continued until the pet is no longer vomiting and is eating, then the treatment is the same as for uncomplicated diabetes. Insulin comes from different sources including beef or pork pancreas and a human genetically engineered form called Humulin. The availability of animal-source insulins continues to decline. In general, cats and small dogs need insulin injections more frequently, usually twice daily, compared to large breed dogs that may only require one dose of insulin daily. The action of insulin varies in each individual and some large dogs will need 2 insulin shots daily. The insulin needs of the individual animal are determined by collecting small amounts of blood for glucose (sugar) levels every 1-2 hours for 12-24 hours. This is called an insulin-glucose-response curve. When insulin treatment is first begun, it is often necessary to perform several insulin-glucose-response curves to determine: The animal's insulin needs may change over time requiring a change in insulin type or frequency of injection. Insulin- glucose- response curves are usually performed several days after a change in insulin is made. Before you give insulin injections to your pet, your veterinarian will show you how to: Insulin is fragile and will become less effective or even inactive, if it gets too hot or cold, or is shaken vigorously. Pay attention to the expiration date on the bottle. Discard insulin that is outdated. You may be able to practice using water and giving the "shot" to an object such as a piece of fruit until you are comfortable using needles, syringes and drawing accurate amounts of fluid into a syringe. Insulin syringes can fill to hold: Remove the syringe and needle from the outer wrapping. Do not remove the needle cap until you are ready to draw insulin into the syringe. The smallest lines between the numbers on a 100 unit syringe, measure 2 units of insulin. 30 unit syringes are numbered by 5's; 5, 10 , 15, etc. The smallest lines between the numbers on a 30 unit syringe, measure 1 unit of insulin. The insulin bottle should not be shaken but rather gently rolled between your hands to mix the insulin in the bottle. Hold the syringe between the thumb and index finger. Pull back on the plunger to the desired dose level drawing some air into the syringe. You can either pull back the plunger using the middle finger of the hand holding the syringe or... Place the needle in the center of the rubber stopper. If the needle is not centered you may be trying to force the needle through the metal ring that is holding the rubber stopper in place and will break the needle. The air is placed in the bottle so a vacuum does not form in the bottle which makes it more difficult to draw insulin from the bottle. If there is only a small amount of insulin left in the bottle, you may only be able to insert the needle into the bottle part way or else you will pass through the fluid and into the air in the bottle. Draw back on the plunger to the correct dose using your middle finger to pull back the plunger. Remove the syringe and needle from the insulin bottle. Holding the syringe with the needle pointed up, gently "flick" the syringe to get the air to rise to the top. Usually the skin is not cleansed before inserting the needle. If the cat has a normal immune system, the few bacteria that are pushed under the skin with the needle will be killed by the cat's immune system. You can use alcohol on a cotton ball to make the hair lay flat so it is easier to see where the hair ends and the skin starts. Alcohol takes about 30 minutes before bacteria are killed, so just swiping the hair with alcohol is not effective in killing bacteria. If you get neither air nor blood, the needle is placed correctly and you can push the plunger to inject the insulin. Give the insulin shots in different locations each time. Syringes and needles used to give insulin should not be discarded in the trash but should be placed in a puncture-proof container and taken to your veterinarian for disposal. Insulin injections are not as perfect as the insulin produced by the pancreas. Blood sugar levels will not always be normal in diabetic pets. The goal of treatment is to reduce the signs of diabetes. When diabetes is well controlled with insulin, the pet should drink, eat and urinate normal amounts. They should have a good appetite, without becoming fat and should have normal activity. Insulin needs are closely related to the type of food eaten by the pet. Your veterinarian will recommend a specific diet and feeding regimen that will enhance the effectiveness of insulin. If your pet is overweight, s(he) will be placed on a weight-reducing diet. As the pet loses weight, less insulin will be needed. Only feed the recommended diet..NO table scraps or treats that are not part of the recommended diet. Heavy exercise will reduce the amount of insulin needed. It is important to talk to your veterinarian before making changes in diet or exercise. There is always some risk that a diabetic patient will develop low blood sugar. Signs of low blood sugar include weakness, staggering, seizures, or just being more quiet than usual. You should keep corn syrup on hand to rub on the animals gums if they have signs suggestive of low blood sugar. Don't pour large amounts of corn syrup in the mouth of an animal that is not fully conscious as the syrup may be inhaled into the lungs. Because insulin needs vary with the activity and lifestyle of your pet, you may want to keep a written daily log of: Your veterinarian may ask you to check your pet's urine for sugar using a test strip. If your pet is well regulated on insulin, the sugar readings in most urine samples will be negative or trace. The strips may have color pads only for glucose or for glucose and ketones. The strip is placed in fresh urine and the color change compared with the colors on the bottle. Be sure to follow the label instructions for timing when to read the results. You should never change the dose of insulin based on the urine sugar reading alone. Animals can have lots of sugar in their urine either when the insulin dose is too low or is too high. There are many styles of machines used to measure blood sugar. The machines are called glucometers. They use color sticks which are read by the glucometer rather than by color changes you can see. Different styles of glucometers use different color strips. Diabetes is rarely reversible in dogs, but diabetic cats will sometimes regain the ability to produce their own insulin in the pancreas. Cats that developed diabetes after receiving long term glucocorticoids or hormones are more likely to stop needing insulin after a while compared to cats that developed diabetes without a known cause. You should have your diabetic pet evaluated by a veterinarian at 2-4 month intervals or anytime another health problem develops. The development of other health problems will often interfere with insulin regulation.

Diabetes is managed long term by the injection of insulin by the owner once or twice a day. Some diabetic cats can be treated with oral medications instead of insulin injections, but the oral medications are rarely effective in the dog. There are three general types of insulin used in dogs and cats:

Not all syringes used to inject insulin are alike. When you buy additional supplies, make sure that you buy the right kind of syringes. Insulin needles are very thin to reduce discomfort during injection.

The syringe is packaged in sterile paper or plastic wrapping or in a plastic case. The needle is covered with a plastic cap to keep it sterile. Use a new syringe-needle combination for each injection.

Insulin syringes have the needle attached. The needle is covered with a plastic cap to prevent the needle from puncturing the wrapping and to keep the needle from bending or breaking.

The plunger fits inside the hollow barrel of the syringe and is pulled part way out of the barrel to draw insulin into the syringe. The plunger is pushed into the barrel of the syringe to push insulin through the needle. The finger grip makes it easier to hold the syringe.

100 unit syringes are numbered by 10's; 10, 20, 30, etc.

The position of the TOP of the black rubber stopper on the plunger is used to measure the volume of insulin in the syringe. The TOP of the black rubber stopper is the part closest to the needle.

Before each injection,

Remove the plastic cap from the needle.

Hold the syringe in your left hand between the thumb and index finger and use the thumb and index finger of the other hand to pull the plunger or...

Place your index finger against the finger grip and pull the plunger with your thumb and middle fingers.

Hold the insulin bottle upside down in your left hand if you are right handed (opposite for left-handed individuals).

Use your thumb to push the plunger and inject the air into the bottle.

Insert the entire length of the needle into the insulin bottle as long as the tip of the needle is in the fluid in the bottle. Insulin needles are very thin and easily bent. You are less likely to bend the needle while drawing insulin into the syringe, if the needle is inserted all the way into the bottle.

If it is difficult for you to pull the plunger with your middle finger, you can use the thumb and index finger to pull the plunger. So that you do not pull the needle out of the bottle, curl the three fingers of your right hand that are not holding the bottle around the syringe trapping it against your palm. Then pull the plunger with the thumb and index finger. Your fingers may be covering the numbers on the syringe so draw more than you need, then push the extra back into the bottle, until the correct amount remains in the syringe.

...or place your index finger against the finger grip to keep the needle from pulling out of the bottle and pull the plunger with your thumb and middle fingers.

If there is an air bubble in the syringe, draw a little more insulin than the correct dose.

Press the plunger with your thumb to push the air out of the syringe, until the correct amount of insulin remains in the syringe.

This 30 unit syringe has been filled to 14.5 units.

There is 1 unit between each back line on this smaller syringe. Smaller syringes allow for more accurate measurements of small amounts of insulin. The top of the black rubber stopper is half way between 14 and 15 units.

This 100 unit syringe has been filled to 48 units. There are 2 units between each black line on the barrel. The volume is measured at the TOP of the black rubber stopper on the plunger.

Pinch up a fold of skin anywhere along the neck or back using your left hand if you are right-handed. Use your right hand to place the needle into the skin fold along the long axis of the fold.

If you place the needle in the opposite direction, across the skin fold, it is more likely that the needle will go through one fold of skin and out the other fold of skin, or may poke into your finger.

Pull back the plunger. If you get air, you placed the needle through both folds of skin. Remove the needle and try again. If you get blood, the tip of the needle is in a blood vessel. Remove the needle and try again.

The top color pad is to read urine sugar. This sample is negative for sugar. The bottom color pad is for ketones and is also negative for ketones.

The glucose pad has turned brown indicating a large amount (>2000mg/dl) of sugar in the urine. The urine is negative for ketones.

If your pet is difficult to regulate with the proper dose of insulin you may be taught how to take a small blood sample from your pet to measure blood sugar readings at home.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is the passing of loose or liquid stool, more often than normal. Diarrhea can be caused by diseases of the small intestine, large intestine or by diseases of organs other than the intestinal tract. Your ability to answer questions about your pet's diet, habits, environment and specific details about the diarrhea can help the veterinarian narrow the list of possible causes, and to plan for specific tests to determine the cause of diarrhea. (Anatomy of the digestive system: dog / cat)

Small intestinal and large intestinal diarrhea have different causes, require different tests to diagnose and are treated differently. Small intestinal diseases result in a larger amount of stool passed with a mild increase in frequency; about 3 to 5 bowel movements per day. The pet doesn't strain or have difficulty passing stool. Animals with small intestinal disease may also vomit and lose weight. Excess gas production is sometimes seen and you may hear the rumbling of gas in the belly. If there is blood in the stool it is digested and black in color. Disease of the large intestine including the colon and rectum cause the pet to pass small amounts of loose stool very often, usually more than 5 times daily. The pet strains to pass stool. If there is blood in the stool, it is red in color. The stool may be slimy with mucus. The pet does not usually vomit or lose weight with large bowel diarrhea. A sudden onset of small intestinal diarrhea may be caused by viruses including canine distemper, canine parvovirus, canine coronavirus, feline panleukopenia virus or feline coronavirus, in young, poorly vaccinated pets. Small intestinal diarrhea can be caused by bacteria such as salmonella, clostridia or campylobacter although these same bacteria can be found in the stool of normal dogs and cats. Worms and giardia can cause small intestinal diarrhea, mostly in young animals. Foreign bodies including bones, sticks and other objects can pass through the stomach and get stuck in the intestine causing both diarrhea and vomiting. These same foreign materials may pass through the intestinal tract without getting stuck but may damage the lining of the intestinal tract causing diarrhea. Dietary indiscretion or a sudden change in diet can cause diarrhea with or without vomiting. Food allergies in dogs and cats can cause diarrhea, vomiting or itchy skin. Toxins including lead and insecticides can cause diarrhea usually with vomiting. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) occurs commonly in both dogs and cats. In IBD the walls of the intestine contain abnormal numbers of inflammatory cells which can be eosinophils, lymphocytes or plasma cells. The cause of IBD is not known but is suspected to be an allergic reaction to components of food, bacteria or parasites. IBD can be congenital in some breeds of dogs, for example Basenji dogs may develop a severe inflammatory bowel disease. Tumors of the intestine are another cause of diarrhea usually occurring in older pets. The tumor may be a single mass when the tumor is from the glands of the intestine (adenocarcinoma) and may be removed by surgery or the tumor may occur diffusely along the intestine. Lymphosarcoma occurs in both dogs and cats and can either be a single or multiple masses in the intestine or the abnormal lymphocytes may be spread through out the intestine. Lymphosarcoma is often responsive to anti-cancer drugs in cats but rarely responds to anti-cancer drugs in dogs. In certain parts of the country small intestinal disease can be caused by fungal infections including histoplasmosis. Your veterinarian can discuss with you whether histoplasmosis is seen in your part of the country. Diseases outside the intestinal tract that may cause diarrhea include kidney failure, liver failure, pancreatic disease and hyperthyroidism in the cat. Severe inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis) can lead to damage of the pancreas and an inability to make enough enzymes to digest fat. This is called pancreatic insufficiency and causes diarrhea with a large volume of greasy stool. Pancreatic insufficiency can occur in young animals due to a congenital deficiency of pancreatic enzymes. The cause of small intestinal diarrhea may be determined from blood tests, examination of the stool, x-rays or ultrasound of the abdomen or by endoscopy. Endoscopy is the technique of passing a flexible scope through the stomach into the upper intestine. Small biopsies of the lining of the intestine can be taken for microscopic evaluation. Endoscopy requires general anesthesia. A diagnosis of intestinal lymphosarcoma may be missed on endoscopy as the biopsies taken using endoscopy do not include the full thickness of the wall of the intestine and the cancerous cells may be deep in the wall of the intestine. A diagnosis in that case requires surgery in order to take a larger biopsy of the entire thickness of the intestine. Dogs and cats with chronic small intestinal diarrhea will lose weight as they are unable to properly absorb nutrients and may develop edema of the legs or fluid accumulation in the belly or chest. A small protein, albumin may be lost in diarrhea. Albumin acts like a sponge to keep water in the blood vessels. When albumin is lost in the stool, blood albumin gets low and water leaks out of blood vessels to accumulate in other locations. Chronic diarrhea may cause the fur to look dull and brittle due to nutrient deficiencies. Acute small intestinal diarrhea can be managed by withholding food, but not water for 24 - 48 hours. If diarrhea stops, small amounts of a bland low-fat food are fed 3 to 6 times daily for a few days, with a gradual increase in the amount fed and a gradual transition to the pet's normal diet. Foods designed as intestinal diets usually contain rice as rice is more digestible than other grains. You are discouraged from administering over-the-counter diarrhea medications without first consulting a veterinarian. If the pet is active, not dehydrated and has been previously healthy, acute diarrhea can often be managed at home. Diarrhea that continues for more than a few days or is accompanied by depression or other signs is an indication to take your pet to a veterinarian. Diarrhea of large intestinal origin can be caused by whipworms, polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, colonic ulcers or colonic cancer. Stress can cause large bowel diarrhea in excitable dogs. The diagnosis of large intestinal diarrhea is also made by blood tests and examination of the stool. A rectal examination using a gloved finger may provide some information about the cause of large bowel problems including rectal polyps and rectal cancer. Endoscopy to examine the large intestine is performed using a rigid or flexible scope passed up the rectum. Because the rectum is often very irritated, colon exams are usually performed under general anesthesia. The treatment of large bowel diarrhea may be based on a specific diagnosis. Non specific treatment of large bowel diarrhea often includes a high fiber diet and sullfasalazine, an anti-inflammatory drug. Black Earth Veterinary Clinic assumes no liability for injury to you or your pet incurred by following these descriptions or procedures.

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM)

Anatomy of the heart of a cat

HCM is a disease that causes thickening of the heart muscle resulting in poor relaxing and filling ability. As the heart’s pumping chamber (ventricle) becomes progressively thicker, less blood can enter the chamber; thus, less blood is ejected out to the body. The cause of HCM is unknown, although certain breeds of cats appear to be predisposed. Middle-aged male cats may be more commonly affected. Sometimes heart muscle thickening similar to HCM can develop secondary to other disorders such as hyperthyroidism (elevated thyroid hormone) and systemic hypertension (elevated blood pressure). Blood pressure measurement and, in cats over five years of age, a blood thyroid hormone test should be done to exclude these secondary causes when cardiac hypertrophy (thickening) is diagnosed.

Some pets show no sign of illness, especially early in the disease. In other cases, signs of left-sided congestive heart failure (fluid accumulation in the lung) may occur. These signs include lethargy, decreased activity level, rapid and/or labored breathing and possibly open mouth breathing with excitement or exercise. Sometimes left and right-sided congestive heart failure develop with fluid accumulation inside the chest or abdominal cavity causing greater respiratory (breathing) effort and abdominal distention. Once fluid accumulations have occurred, clinical heart failure is present and aggressive medical therapy should be sought. Other signs of this disease can include sudden weakness, collapsing episodes, and unfortunately even sudden death due to disturbances in heart rhythm. In some cats with a very large heart chamber (i.e. left atrium) a blood clot may form and if it enters the circulation may cause weakness or paralysis (usually of the rear legs). If this occurs, contact your veterinarian right away to determine if complications related to heart disease (or another disease) are present. A physical examination performed by your veterinarian may reveal a heart murmur, abnormal heart sounds, abnormal lung sounds, or irregularities in heart rhythm. Chest radiographs (x-rays), an electrocardiogram (ECG..sometimes called an EKG), and an echocardiogram (heart ultrasound) are tests often utilized to confirm a suspected diagnosis and to determine severity. A routine physical exam and one or more of these tests may be recommended every six months to one year to look for any progression of disease in cats without clinical signs. Asymptomatic pets may not need medical therapy depending on the findings of the tests listed above, but routine reevaluations will often be recommended. Other cats will need medications to slow the heart rate, and promote relaxation of the pumping chambers (ventricles). If arrhythmias or congestive heart failure signs are present, additional medications used may be required. Since this disease can be progressive, the number and the amount of medications used may change with time. Therapy is always tailored to the needs of the individual patient. If congestive heart failure is present, dietary salt reduction is also recommended. Medications commonly used for HCM: Beta-adrenergic blockers such as atenolol (Tenormin) or propanolol (Inderal). These medications slow the heart rate, which enhances filling and relaxation of the pumping chambers. Beta-blockers also allow more time for blood flow to the heart muscle itself, and reduce the amount of oxygen used by the heart. In some cases, the incidence of arrhythmias is also lessened. Side effects may include bronchospasm (spasm of the airways) (propranolol), fatigue, and in excessive doses, slow heart rate and low blood pressure. Calcium-channel blockers such as diltiazem (Cardizem CD, Dilacor XR). This class of drug has similar actions to the beta-blockers. Some differing characteristics of the calcium-blockers include little or no anti-arrhythmic activity in some cases, possible a greater ventricular relaxing effect, and a greater propensity for low blood pressure at higher doses. Other medications may be prescribed in some patients. Diuretics (furosemide, spironolactone, etc.) may be needed to control edema and effusions (congestive heart failure). In pets that have had or may be prone to blood clot formation, anti-coagulants such as aspirin, warfarin, or heparin may be prescribed. Medical therapy is always chosen to meet the needs of the individual patient. Frequent recheck examinations and adjustments may be needed especially early in the course of treatment to individualize a medication regimen. This Pet Health Topic was written by O. L. Nelson, DVM, MS, Diplomate ACVIM (Cardiology & Internal Medicine) Washington State University.

Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM)

What is it?

DCM is a disease of the heart muscle that results in weakened contractions and poor pumping ability. As the disease progresses the heart chambers become enlarged, one or more valves may leak, and signs of congestive heart failure develop. The cause of DCM is unclear in most cases, but certain breeds appear to have an inherited predisposition. Large breeds of dogs are most often affected, although DCM also occurs in some smaller breeds such as cocker spaniels. Occasionally, DCM-like heart muscle dysfunction develops secondary to an identifiable cause such as a toxin or an infection. In contrast to people, heart muscle dysfunction in dogs and cats is almost never the result of chronic coronary artery disease ("heart attacks").

What are the signs of this disease? Early in the disease process there may be no clinical sign detectable, or the pet may show reduced exercise tolerance. In some cases, a heart murmur (usually soft), other abnormal heart sounds, and/or irregular heart rhythm is detected by your veterinarian on physical examination. Such findings are more likely as the disease progresses. As the heart’s pumping ability worsens, blood pressure starts to increase in the veins behind one or both sides of the heart. Lung (pulmonary) congestion and fluid accumulation (edema) often develop behind the left ventricle/atrium. Fluid also may accumulate in the abdomen (ascites) or around the lungs (pleural effusion) if the right side of the heart is also diseased. When congestion, edema and/or effusions occur, heart failure is present. Weakness, fainting episodes, and unfortunately, even sudden death can result from heart rhythm disturbances (even without "heart failure" signs). What are the signs of heart failure? Dogs with heart failure caused by DCM often show signs of left-sided congestive failure. These include reduced exercise ability and tiring quickly, increased breathing rate or effort for the level of their activity excess panting, and cough (especially with activity). Sometimes the cough seems soft, like the dog is clearing its throat. Poor heart pumping ability and arrhythmias can cause episodes of sudden weakness, fainting, or sudden death as noted above. Some dogs with DCM experience abdominal enlargement or heavy breathing because of fluid accumulation in the abdomen or chest, respectively. Presence of any of these signs should prompt a visit to your veterinarian to determine if heart failure (or another disease) has developed. More advanced signs of heart failure could include labored breathing, reluctance to lie down, inability to rest comfortably, worsened cough, reduced activity, loss of appetite, and collapse. A veterinarian should be consulted right away if these signs occur. Signs of severe heart failure may seem to develop quickly with DCM, but the development of underlying heart muscle abnormalities and progression to overt heart failure probably takes months to years. How is this disease diagnosed? A cardiac exam by a veterinarian can detect abnormal heart sounds (when present) and many signs of heart failure. Usually chest radiographs (x-rays), an electrocardiogram (ECG), and echocardiogram are performed to confirm a suspected diagnosis and to assess severity. Echocardiography also can be used to screen for early DCM in breeds with a higher incidence of the disease. Resting and 24-hour (Holter) ECGs are sometimes used as screening tests for the frequent arrhythmias that usually accompany DCM in some breeds, especially boxers and Doberman pinchers. What can be done if my pet has this disease? Asymptomatic (subclinical) cases of DCM may be treated with enalapril or another ACE inhibitor to slow progression of the changes leading to heart failure. Other medications and strategies are also used as signs of heart failure develop and/or if rhythm abnormalities are present. Therapy is always tailored to the needs of the individual patient. Since this disease is not reversible and heart failure tends to be progressive, the intensity of therapy (for example, the number of medicines and the dosages used) usually must be increase over time. This Pet Health Topic was written by O. L. Nelson, DVM, MS, Diplomate ACVIM (Cardiology & Internal Medicine) Washington State University.

Heart Valve Malfunction in the Dog (Mitral Insufficiency)

Many dogs slowly develop degenerative thickening and progressive deformity of one or more heart valves as they age. In time, these changes cause the valve to leak. The mitral valve is most commonly affected. This valve separates the blood collecting chamber (left atrium) from the pumping chamber (left ventricle) leading to the body. Some dogs also develop these changes in the tricuspid valve, which separates the collecting (right atrium) and pumping (right ventricle) chamber leading to the lungs.

Certain breeds have an inherited predisposition to this disease. Degenerative valvular disease is slowly progressive over years and is non-reversible. The volume of blood that leaks back into the atrium with each heartbeat tends to increase slowly over time. However, many dogs with this disease never develop signs of congestive heart failure even though they may have a loud murmur. Early in the disease process, your veterinarian may hear a soft murmur when the affected valve starts to leak. There usually is no noticeable change in the dog’s activity level or behavior for a long period of time. Gradually, though, the valve leak tends to get worse and the heart slowly enlarges. If the leak becomes severe, blood may start to back up behind the heart – usually into the lungs. This causes lung congestion and fluid accumulation (edema). When lung congestion and edema occur, congestive heart failure is present. Reduced exercise ability may be the first sign of heart failure. Most dogs with heart failure caused by degenerative valve disease show signs of "left-sided" congestive failure. These signs include tiring quickly, increased breathing rate or effort for the level of activity, excessive panting, and cough (especially with activity). The presence of any of these signs should prompt a visit to your veterinarian to determine if heart failure (or another disease) has developed. More advanced signs of heart failure could include labored breathing, reluctance to lie down, inability to rest comfortably, worsened cough, reduced activity, and loss of appetite. Your veterinarian should be consulted right away if these signs occur. Some dogs that become symptomatic from their heart disease develop fluid in the abdomen (ascites); others have episodes of sudden weakness or fainting that can result from irregular heartbeats or other complications. As long as no sign of heart failure develops, no treatment is necessary, although reduction of dietary salt intake is often advised. Again, there are many dogs with degenerative valvular disease that never progress to heart failure. However, if heart failure develops, several medications and other strategies are used to control the signs. Since the disease is not reversible and heart failure, when it occurs, tends to be progressive, the intensity of the therapy (including the number of medicines and dosages used) usually must be increased over time. Therapy is always tailored to the needs of the individual patient. This Pet Health Topic was written by O. L. Nelson, DVM, MS, Diplomate ACVIM (Cardiology & Internal Medicine) Washington State University.

Holiday Health Hazards

If you want to get festive, mix some of your pet's regular food with water to make a "dough" and roll out and cut into festive shapes, then bake until crunchy.

The holiday season brings excitement and commotion associated with shopping, final exams, travel, and other seasonal preparations. In all the activities of the season our beloved pets may be exposed to hazards less commonly found other times of the year. As homes fill with holiday spirit, pets may be intrigued by the new sites, smells and tastes. The following are some of the most common health concerns for your pet during the holidays. If you have specific questions regarding any pet health concern please contact your veterinarian.